The Supreme Court has agreed to hear TikTok’s emergency appeal to block the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act, colloquially referred to as the “TikTok ban.” Oral arguments will be heard on January 10, 2025, nine days before the ban is set to take effect.

Let’s take a look at the legislative, executive and judicial decisions that have framed this battle of free speech versus national security.

History

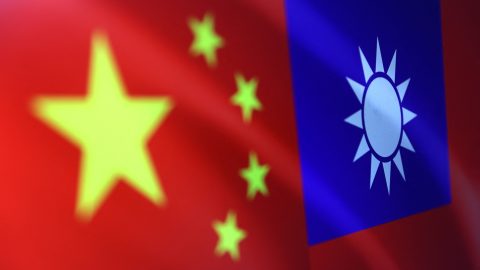

In 2018, ByteDance — a Chinese company — launched TikTok in the U.S. Since then, TikTok has blown up, boasting 170 million monthly users (mostly teens and twenty-somethings) who post and watch videos ranging from hair care routines to gaming to political commentary.

In addition to capturing the attention of the American youth, TikTok has attracted government scrutiny and concern over potential national security vulnerabilities that the app creates. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) began investigating TikTok in 2019. After CFIUS determined in August 2020 that TikTok could not sufficiently mitigate the government’s national security concerns, then-President Donald Trump issued an executive order seeking to limit ByteDance’s influence in the U.S. Two courts found that Trump’s order exceeded his authority.

Government scrutiny of TikTok continued and intensified during the administration of President Joe Biden. TikTok proposed a national security agreement to quell the government’s concerns in 2022 but Biden rejected it. This agreement would 1) create operational independence from ByteDance, 2) restrict the types of American data accessed by ByteDance, 3) allow for Oracle to review TikTok’s source code, and 4) give the government a “kill-switch” for TikTok’s U.S. operations.

Nevertheless, TikTok implemented some of its proposed measures. It migrated the U.S. version of TikTok to the Oracle cloud, implemented stricter data access controls and created an independent oversight body to ensure compliance with U.S. regulations.

In April, Biden signed into law the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act. The act makes it “unlawful for an entity to distribute, maintain, or update” a foreign adversary-controlled application (TikTok is the only app that has been designated as such). The act includes an exemption for “qualified divestitures,” where the president determines that the app is no longer controlled by the foreign adversary. The act gave TikTok until January 19, 2025 to divest itself of its U.S. business or be banned.

D.C. Circuit Decision

Rebuffed by the White House and Congress, TikTok asked the courts to declare that the Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act violates the Constitution. The case was heard by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit and decided on December 6. The court rejected each of TikTok’s constitutional claims, the most significant one being about the First Amendment.

This case boiled down to a decision about how to balance the constitutional right to free speech and the government’s interest in protecting national security. TikTok had three main arguments: 1) by effectively banning TikTok — a platform for self-expression — the Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act violates TikTok’s and 170 million Americans’ right to free speech; 2) the government does not have a legitimate national security interest and is instead motivated by questionable, if not illicit, desires to restrict Americans’ access to particular content that appears on the app; and 3) TikTok’s national security agreement satisfies national security concerns and is a less extreme alternative to divestiture.

On the other hand, the government claims that TikTok poses a serious national security threat to the U.S. by creating two vulnerabilities that the Chinese government can exploit. First, is the risk that the Chinese government accesses and misuses American data via TikTok. Second, the Chinese government may compel TikTok to manipulate the content on the platform to influence the thinking of Americans.

Regarding the government’s concern about data collection, TikTok maintains that the government is misconstruing its data practices and presenting only speculative evidence that its data policy poses a national security threat.

The court concluded that:

- The government’s data-related justification is compelling, citing recent cases involving China’s use of state-connected “information technology firms as systemic espionage platforms” and other empirical evidence that the Chinese government leverages its relationship with domestic companies to collect foreign data.

- The government doesn’t need to wait for a risk to materialize to make an informed judgement about the national security risks of TikTok’s data collection practices.

- TikTok “misses the forest for the trees” by not addressing the government’s overarching data security concern, which is that even if TikTok was able to claim that they could perfectly secure American data, the government would have no way to reliably confirm this. As long as TikTok’s U.S. business remains tied to the ByteDance, the Chinese government can compel it to hand over American data.

On covert content manipulation, TikTok’s main arguments are twofold. First, that the government aims to suppress particular content by banning TikTok or forcing it to divest. Here, TikTok references comments made by legislators in committee hearings leading up to the passage of the Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act that convey a distrust/dislike of particular content on the app. TikTok claims that the government’s real motive is “to control the flow of information to the public.” TikTok also argued that the government intentionally didn’t give TikTok enough time to divest, which makes the Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act effectively a ban, in turn betraying the government’s real motive to censor the content on the app.

The court concluded that:

- Even if some legislators had illicit motives, the Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act still supports a legitimate national security interest. Precedent instructs that courts should “not strike down an otherwise constitutional statute on the basis of an alleged illicit legislative motive.”

- A divestiture would not necessarily change the content displayed by TikTok at all, it would simply ensure that the Chinese government doesn’t have a hand in manipulating it.

- 270 days is enough time to divest and TikTok can divest after 270 to lift the ban.

Second, TikTok argued that the government’s claims that China could manipulate TikTok’s content are speculative and some of the government’s claims are inaccurate, primarily that the algorithm that dictates what U.S. users see on TikTok is based in China.

The court concluded that:

- Even if the government lacks concrete evidence, it has enough evidence to make an “informed judgement” about the threat that TikTok poses. Specifically, the government has evidence that the Chinese government had manipulated content somewhere “outside of China.”

- The fact that TikTok never squarely denies that it has ever manipulated content at the direction of the Chinese government is “striking” and serves the government’s argument that it may not have concrete evidence simply because the government doesn’t have a reliable way to monitor the platform.

- Even if TikTok’s recommendation engine resides in the Oracle cloud, the algorithm is formulated through collaboration with engineers in China.

Finally, the court decided to defer to the government’s judgement that TikTok’s national security agreement — which TikTok proposed to the court as a less restrictive alternative to divestment — could not sufficiently address the government’s concerns for the reasons described above. In short, the court found that the Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act does not violate the First Amendment due to a compelling national security interest and the lack of a less restrictive alternative.

The court was resoundingly supportive of the government’s arguments. But the Supreme Court could alter TikTok’s fate. Millions of Americans will be anxiously awaiting whatever unfolds next month. As Chief Judge Sri Srinivasan put it in his opinion concurring in the judgment, “if no qualifying divestment occurs — including because of the PRC’s or ByteDance’s unwillingness — many Americans may lose access to an outlet for expression, a source of community, and even a means of income.”

Leave a Reply