When it was released earlier this month, the U.K.’s “external” Strategic Defence Review called for a “whole-of-society” approach to unconventional warfare, including cyberattacks and attacks on infrastructure. Tellingly, part of that approach included “building industrial and supply chain resilience.”

The document does not mention the renewable energy supply chain by name, but if recent statements from some around the top of the British state are anything to go by, they were likely to be in mind.

In a briefing at the U.K. Parliament last month, former British diplomat Charles Parton warned against allowing China access to the national grid, saying: “It wouldn’t be difficult in a time of high tension to say, ‘by the way, we can turn off all your wind farms.’”

At the same briefing, Richard Dearlove, the former head of MI6, suggested national infrastructure, such as hospitals, energy grids and transport networks, could come “under the control of the Chinese Communist Party.”

And these are not just discussion points. A U.K. government review of China’s role in energy systems like solar panels is ongoing, with reports MI5 is analyzing how technology such as solar panels or industrial batteries could generate security threats.

So, are these concerns about reliance on China for renewable energy infrastructure credible?

Rogue Communication Devices

One piece of evidence appeared to suggest the answer is “yes” last month, when Reuters reported that U.S. energy officials had found “rogue communication devices” in Chinese solar power inverters. Those are the devices that help connect solar panels to national grids and “That effectively means there is a built-in way to physically destroy the grid,” one person familiar with the investigation told Reuters.

However, the issue is not straightforward. Former chief scientific advisor for national security Anthony Finkelstein responded to the Reuters report in a blog that suggested the communication device was unlikely to have been placed there deliberately, but that poor engineering could nevertheless be exploited.

“Supply chain attacks are extremely difficult and costly to mount” and are “liable to discovery” Finkelstein wrote. But “bad engineering is as much of a threat as malicious implant. Indeed, perhaps more.” Because “vectors of attack are multiplied and difficult to discern” and “The situation is exacerbated if your adversary is aware of the bad engineering and is better positioned to exploit it than you are to mitigate it.“

So, there is a view that even without malicious intent there is a problem.

“I see the primary vector as poor engineering which bears the risk of being weaponised in a situation of international tension,” Finkelstein summarized in an email to Domino Theory. “I generally favour lessening our dependence on Chinese technology, in a proportionate manner. I argue strongly that we should build for resilience — assuming components are untrusted.”

Sam Dunning, director of U.K.-China Transparency, elaborated on this view.

“I think the key is to understand that if a whole load of components are made and designed in China, and are imperfect in software/hardware and therefore contain potential vulnerabilities, then it is likely that it is the manufacturers, with their obligation to work with Chinese security services, that would be best placed to understand the exact nature of those vulnerabilities,” Dunning said.

“[I]t is the Chinese security services, with their proximity to the manufacturers, authority to compel cooperation and resources to offer incentives for cooperation, that would be best placed to exploit those vulnerabilities.”

Dunning added that this concern is not incompatible with those expressed by the likes of Dearlove and Parton. Poor quality engineering can be a problem alongside malicious intent.

Tim Law, deputy director at U.K.-China Transparency, added by email that in his experience, Chinese Communist Party “entities are quite fastidious in their desire not to be easily (or at all) identified as the originator of any form of attack through cyber mechanisms.” So things that look like accidents might not always be.

“Vulnerabilities exist within any digital system, whoever designs and builds it. It’s the degree to which trust is established in terms of over-the-air access to systems in place within the West that is the issue,” Law added.

But other views are available, too.

Alternative Views

One of the responses within the renewable sector is to emphasize that there are risks with any kind of energy imports. Conflict between Iran and Israel has long been marked as a threat to stable oil and gas prices, for instance, and Israel’s escalation sparked the largest single-day oil price rise in three years. Shell’s chief executive, Wael Sawan, is now warning that if the Strait of Hormuz is blocked it could shock energy markets.

“Of course, there are risks. There are risks with any external supplier — and internal ones for that matter (domestic energy companies in Britain can exploit monopolies for instance).” Kerry Brown, former British diplomat and professor of Chinese Studies at Kings College London’s Lau China Institute, told Domino Theory by email.

“These things have to be seen on a spectrum. The sensible thing would be to have diversity of supply, no overreliance on China while there are such significant security differences. But getting in a major panic about China no matter what sector, what issue, and what scale, risks becoming as big, if not a bigger issue, than the claimed problems China is meant to be posing for us!”

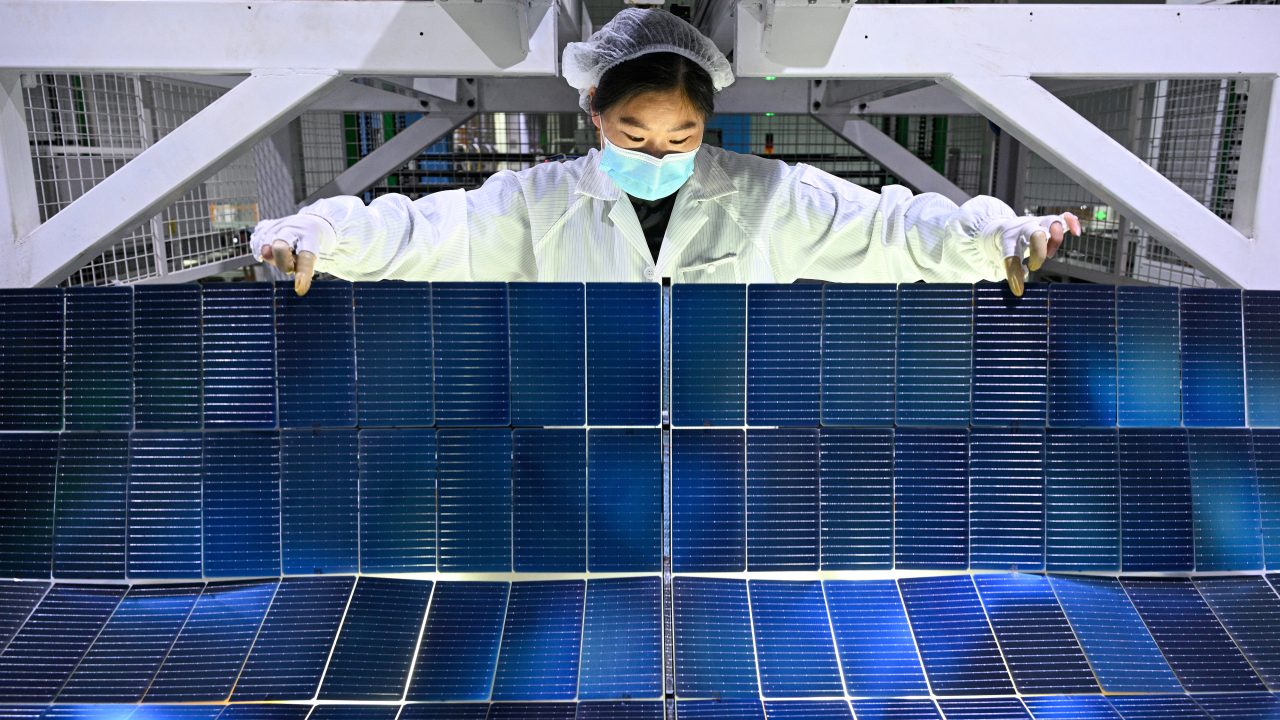

Brown’s point is underscored by the position China occupies in solar supply chains. It is not simply a key player. It is the dominant player to the extent that “if you want to be serious about addressing Britain’s energy needs and doing this by using solar, China is hard to avoid.”

China’s share in all the manufacturing stages of solar panels is over 80%. And when Domino Theory spoke with Solar Energy U.K. last year, its spokesperson was clear that there was no prospect of replacing solar imports any time soon.

Kerry’s view is that the likes of Parton and Dearlove are “purists” who “tend to look at all these things from a pure security lens where it is all or nothing.” And this is not unsubstantiated. Neither Dearlove or Parton named alternatives to sourcing solar from China in their public comments. Neither did Member of Parliament Ian Duncan Smith when he criticized the renewable sector’s reliance on China last year. And neither did the U.K.’s Strategic Defence Review.

The Future of Green Energy

If one does not take the position that green energy is an indulgence that can simply be ignored, then, there is potentially a black hole of policy here.

For its part, there has been some indication of what the much-maligned — and China agnostic — U.K. government is thinking in recent days. It just moved £2.5 billion from its renewable energy investment vehicle, Great British Energy, over to its vehicle for building nuclear power plants — at the same time as ruling out Chinese investment in its latest nuclear project.

If that is representative of a broader strategy, there is a long way to go. Nuclear made up just 14.4% of overall power generation in the U.K. last year, and delays and soaring costs have stymied previous efforts to increase that number.

In other words, there are no easy answers that will please everyone. There are trade-offs in every direction.

Correction: Tim Law’s view was mistakenly presented as in opposition to Sam Dunning’s. It was rephrased as an addition.

Leave a Reply