Hong Kong entered its post-Article 23 existence amid a susurrus of revelations that pro-democracy protesters under the age of 21 are being held in detention centers where physical and sexual abuse is perpetrated and condoned.

According to a Facebook post in January by former detainee Wong Yat-chin (王逸戰) as well as more recent interviews published by Radio Free Asia and The Reporter, abuse, including rape and anal assault, occur in Pik Uk Prison. Juveniles who sung “Glory to Hong Kong,” an emblem of the democracy movement, were also “slapped around,” and victims were beaten within earshot of others so that their cries would have an intimidatory effect.

Since informing international organizations of this kind of abuse can now be interpreted as a crime by way of the aforementioned Article 23 laws and Radio Free Asia has now discontinued full-time operations in the city due to unacceptable risks to its staff, there is little to stop such horrors persisting in Hong Kong detention centers, even as the number of people interred in them swells.

A signature of the way dissidents are mistreated in mainland Chinese prisons, much abuse is meted out not by staff, but by privileged inmates who are permitted to discipline others, yet another hint at the suspected entwinement between Hong Kong authorities and the city’s criminal fringe. The price of his outspokenness, Wong has this month posted a video of unidentified men harassing and recording him on the way to the airport and questioned how they knew he was going there.

Such murkiness is characteristic of other incidents such as the July 2019 attack in Yuen Long metro station, when members of the public and protesters alike were beaten by a gang of white-shirted thugs, almost certainly with the prior knowledge of police. This month, an accountant named Jacky Ho (何贊琦), who had gone to the station to protect victims of the attack, was convicted of rioting during the incident, as authorities attempt to portray it as a violent ruckus between rival groups, not a calculated assault on citizens demanding rule of law and a right to vote.

Per District Judge Clement Lee Hing-nin (李慶年), Ho had thrown an umbrella and a soda can at the white shirts, which will contribute to an incarceration of nearly three years. Joining him in jail for preposterous crimes are Joseph John, a Portuguese national, who will not see freedom for at least the next half decade because he has “distorted history, demonized the Chinese government, and appealed to foreign countries to destroy Hong Kong and China” in social media posts, and Yu Yan-yuk (余昕鈺), who was convicted of money laundering for activities that would be more accurately described as crowd funding in less authoritarian jurisdictions. He was 17 at the time of the supposed offense.

These are, of course, examples of individuals who have actually received sentences. Others, such as Chow Hang-tung (鄒幸彤), Lee Cheuk-yan (李卓人) and Albert Ho Chun-yan (何俊仁), who were all members of the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, which advocated for justice over the Tiananmen massacre and democracy in the mainland, are awaiting a trial that never comes, while the verdict in a sedition case against editors of the now-shuttered media Stand News has once more been postponed. Again, this is reminiscent of how Beijing weaponizes court proceedings in China proper to keep opponents in a constant state of limbo, extract confessions and crush opposition hope within a nightmare that never seems to end.

Thus, the judicial system is being subverted to persecute people, and nowhere is that more evident than in the trial of pro-democracy media magnate Jimmy Lai (黎智英), who is facing down charges of conspiring both to collude with foreign forces and publish “seditious” materials. In proceedings that are widely believed to have a predetermined ending, this month witness testimony evidenced that Lai was a powerful voice for non-violent protest, although even such a detail will likely be used to incriminate him as the peaceful approach is cast as a tactic to shore up what China fears most of all — international support.

Beforehand, alleged torture victim Andy Li (李宇軒), who has emerged from Siu Lam Psychiatric Centre to give evidence for the prosecution, completed 15 days of testimony on April 11. Among the more prescient of his statements, he described a feeling prior to his detention by Chinese and Hong Kong authorities that there was no point to giving up activism aimed at securing democracy when a draconian new law was passed in 2020, because “Beijing would move the goalposts” to arrest and charge him by any means anyway.

This image of a territory in which laws are thus designed and interpreted according to the whims of the Chinese Communist Party, where the police, judges and officers in correctional facilities jostle with one another to selectively isolate, imprison and abuse advocates of universal suffrage, is one that Hong Kong is anxious to avoid. Hence, in an unprecedented demonstration of impunity, it has detained, searched and deported a representative for the prominent international press freedom organization Reporters Without Borders (RSF) in order to block her from entering the city to observe the Lai trial.

Authorities are terrified about what RSF would conclude, just as they are determined to avoid responsibility for the climate of fear they have precipitated. Despite getting off lightly for their passage of rights-eroding laws in the eyes of many Hong Kong advocacy organizations, they have still hit out at travel warnings issued by overseas governments such as Canada, which, addressing citizens, bluntly informs, “You risk being arbitrarily detained on national security grounds, even while you are transiting through Hong Kong. You could be subject to transfer to mainland China for prosecution. Penalties are severe and include life imprisonment.”

Somehow, the Hong Kong government believes that, coupled with squeezing the air from the operating environment for journalists, its aggressive stance will be rewarded with a positive international reputation no matter how dictatorial it becomes.

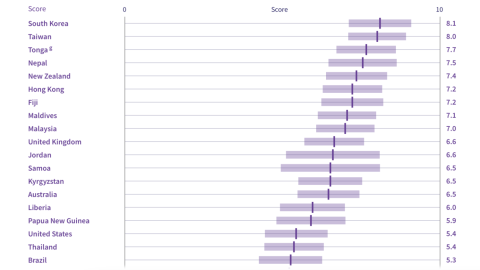

Instead, it is resulting in a culturally embattled city where police rock up to scour identity cards at autograph sessions for pro-democracy singers; dental service providers are ordered to insert national security clauses in third party contracts; attendance at flag-raising ceremonies is allegedly compelled from students on penalty of forgoing math exams in a milieu where academic freedom compares unfavorably with Cambodia, Iraq and Uzbekistan; and government-backed losers from the 2023 district elections are placed in committees that hold special voting and candidate selection privileges for next time.

In its recently published “The State of the World’s Human Rights” report for 2023/24, Amnesty International catalogs a month-by-month stream of ultra-punitive actions Hong Kong has wreaked upon its citizens and surmises the city to have become “ever more curtailed as the authorities maintained wide-ranging bans on peaceful protests and imprisoned pro-democracy activists, journalists, human rights defenders and others on national security-related charges.” Given how the situation has deteriorated from an already low base last year, it is perhaps better not to imagine what the report will read next time around.

Leave a Reply