At a drone warfare symposium hosted at the Legislative Yuan in Taipei on Tuesday morning, there was one point that everyone could agree on: Taiwan needs to build more drones, and it needs to do it fast. By the end of the event, it was clear that deciding how Taiwan will do that is a puzzle too difficult for one two-hour discussion to solve.

Taiwan’s government posted a tender notice last month announcing that the Ministry of National Defense’s Armaments Bureau plans to acquire 50,000 drones over the next two years. New companies, and new divisions within old companies, have been popping up all over Taiwan to meet the growing demand, from model car manufacturers to battery pack packagers.

“50,000 is not going to cut it,” Ellen Chang, Managing Director for Defense Infrastructure at CapZone Impact Investments who sat on the symposium panel, told the conference room. “In fact … maybe you need to multiply that by like 100,000 and maybe that’ll start to actually mobilize the manufacturing lines.”

One thing that might help: As part of its new procurement plan, Taiwan’s defense ministry reclassified drones as “consumables,” which puts them in the same category as ammunition rather than fighter jets. The U.S. made a similar move in July.

Misha Lu (呂亦塵) works in strategic development at Tron Future, a Taiwanese company that specializes in AI-driven anti-drone systems. He was at the symposium on Tuesday, and later said that he agreed with Chang’s assessment. “50,000 drones … is just the beginning,” he said.

Tron Future has started to work on its own drones as well, a plan that Lu sees as a natural evolution for the company. “Anti-drone and drone are two sides of the same coin,” he said. “You have to know drones really well to be able to counter them effectively.”

The event’s attendees came from all over the world, but the symposium isn’t why most of them are in town. The biennial Taipei Aerospace & Defense Technology Exhibition, or TADTE, is set to kick off on Thursday. When it was last held in 2023, nearly 280 companies participated. This year, there will be more than 400. (Domino Theory will provide live updates from the exhibition later this week.)

At the drone symposium on Tuesday, “come see me at my booth later this week” was a common refrain.

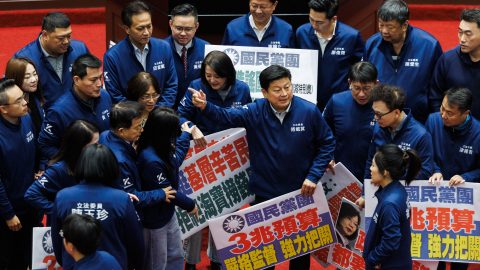

The event was organized by Legislator Chen Kuan-ting (陳冠廷) of Chiayi County, a region in Taiwan’s southwest that is home to the island’s largest drone testing facility. Eric Du, founder of the Formosan Enterprise Institute, moderated the panel.

Chen, who Du introduced as the “czar of unmanned systems in Taiwan,” is a member of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). But he isn’t entirely satisfied with the government’s approach. At one point, Chen recounted questioning Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) on Taiwan’s drone strategy.

“The minister responded that it will not be appropriate to disclose our unmanned system strategy in parliament or in public,” Chen said. “I still remember, I’m holding a copy of the U.K. drone strategy in my hands during the session. What I [meant] was this: We need to understand our current strategic assumptions so that our ecosystem can keep pace.” (On Tuesday, Domino Theory reported that Taiwan’s government ministries have become less transparent in the last two years, a shift they say is meant to protect operational security.)

Lu, the strategist at Tron Future, said after the symposium that ramping up Taiwan’s drone production is an issue not of design, but production. If a key segment of Taiwanese weaponry is going to be unmanned, he thinks its production will have to be, too. “One of the keys is to get the production process automatic,” Lu said.

Another input that drone production should be free of is Chinese parts. That’s according to the tender notice that the defense industry posted last month, which said that firms linked to China would also be barred from the production process. The requirement for a “non-red” supply chain could pose a particular challenge for making aerial drones that rely on high-power battery cells, a market which China dominates.

At an event across town on Tuesday afternoon, Cathy Fang (方怡然), a policy analyst for the National Security and Economic Research Program at DSET, a Taiwanese government-funded think tank, said that Taiwanese drone companies are especially reliant on Chinese components in two areas: rare earths used in permanent magnets, and the anodes used in batteries.

Fang was serving on a panel hosted by the Taiwan Foreign Correspondents Club on Taiwan’s defense industry supply chain with Rupert Hammond-Chambers, president of the U.S.-Taiwan Business Council.

Both Fang and Hammond-Chambers have high expectations for the industry in Taiwan. Fang said that the vision is “to make drones another TSMC for Taiwan.” She wants to make Taiwan’s drone ecosystem, including modules, motors and other components “irreplaceable for the world.”

This ambition might be hard to square with the nascent state of drone manufacturing in Taiwan, and the dominance of Chinese players in the market. Currently, China controls “close to 90 percent of the global commercial drone market,” according to Drone Industry Insights.

But Fang had an answer to that. She recently traveled to Poland and spoke with Polish and Ukrainian drone manufacturers. “They choose China’s DJI [the largest Chinese drone manufacturer] components because they have no alternative,” she said. These companies “can tolerate the increase of costs for 30 percent” to get a trustworthy, “reliable component from Taiwan.”

Hammond-Chambers, for his part, highlighted that conflicting forces determine the necessary pace of Taiwanese drone development. To grow fast enough, he said, Taiwan is going to have to pick areas where it might already have an advantage, while actively seeking to cooperate with the U.S. and Europe.

Even so, Hammond-Chambers said that building up Taiwan’s domestic defense industry will take time.

He predicted that next year will see “an uptick in defense delegations that have American and Taiwan businesses going to third countries to talk about expanding partnerships.” Taiwan very rarely sells military equipment to other countries.

Hammond-Chambers thinks it can happen. “Taiwan’s perfectly capable of building up a robust supply chain, both as a supplier for the international community as well for its own domestic needs.”

Earlier on Tuesday, at the Legislative Yuan, Kai Wu (吳鎧) said that his company has found a niche in that supply chain. Wu is head of finance and strategy at Voltasphere, a battery pack startup hoping to capitalize on the step between battery production and drone procurement. Voltasphere is an American company, but it’s working to package Taiwanese battery cells into thermally efficient packs that it can then sell to Taiwanese dronemakers.

Another American startup in town is HavocAI, which says it is developing systems that will allow a “swarm” of sea drones to operate in concert autonomously.

In a demo video played by HavocAI’s chief strategy officer Ben Cipperley during the panel session, six uncrewed boats spread out in formation in front of a crewed logistics vessel. When an unidentified ship approached from the top-left of the swarm, the uncrewed boats evaded the intruder, then pivoted to maintain their alignment, all without input from the logistics crew.

A report from Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs published earlier this year concluded that fully autonomous weapon systems envisioned for the defense of Taiwan were at least five years away from operational maturity. But Cipperley thinks the tech is ready now.

One advantage of the swarms Havoc is building is that, in addition to being uncrewed, under the right circumstances, they could also be disposable. “When something costs a million and a half dollars, you’re gonna want it back,” Cipperley said after the session. Havoc plans to sell theirs for much less.

“If I use a $2 billion missile to counter a $150,000 drone, do that all day,” he said. “That would be amazing. Eventually they’ll run out.”

A draft of the U.S. National Defense Authorization Act for 2026, which is now awaiting debate in the Senate, calls on the U.S. to establish a joint program with Taiwan for field drones and anti-drone systems. At the Legislative Yuan on Tuesday, it seemed like the market might already be doing the work for them.

Cipperely said that Havoc, which is only 19 months old, has already been in discussion with Taiwanese companies. Autonomous sea drone systems could prove especially fertile ground for the two countries. While American companies lead in AI, the Taiwanese shipbuilding industry remains a juggernaut.

If U.S.-Taiwan cooperation is the future of the drone industry, then Tuesday’s symposium presented a fitting display. Aside from Legislator Chen, all four of the panel members had come from the U.S. That fact was clearly not lost on some members of the audience, which included a sizable contingent from Ukraine, a country whose fight against Russian invasion is largely responsible for the attention drone warfare now receives.

After Du announced that there was time for just one more question, Maria Makarovych, head of the Ukraine Liberal Democratic League’s East Asian Office, rose to put a somewhat ironic bow on the proceedings. “Taiwan doesn’t have experience in developing comprehensive drone infrastructure,” she said, “and moreover, the U.S. doesn’t have it either.”

Leave a Reply