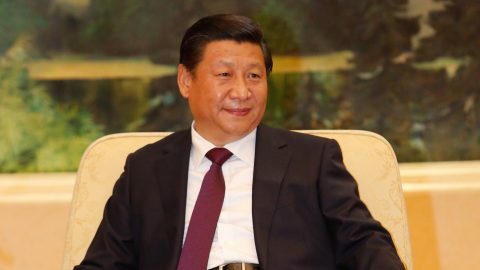

U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer is on his way to Beijing where he will meet with Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) tomorrow. This meeting marks the first visit by a British prime minister to China since Theresa May’s trip in 2018.

During her 2018 trip, May promised to “intensify the golden era in U.K.-China relations” that had been elevated by David Cameron. U.K.-China relations soured under subsequent Conservative governments, punctuated by Covid-19 and other events in 2020 like China’s imposition of national security legislation on Hong Kong and the U.K.’s decision to ban Huawei technology from its 5G networks.

Eight years later, Starmer’s trip to China is being anticipated against the backdrop of U.S. President Donald Trump’s chaffings with other world leaders. When Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney visited Beijing earlier this month, striking a deal with Xi to cut tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, Trump threatened to impose a 100% retaliatory tariff on Canada. “If Governor Carney thinks he is going to make Canada a ‘Drop Off Port’ for China to send goods and products into the United States, he is sorely mistaken,” Trump wrote on Truth Social.

The idea in circulation is that strained relations with Trump are causing U.S. allies, including the U.K., to lean toward Beijing. For some, Starmer’s trip to China offers a chance for him to redefine the U.K.’s global role in light of Trump’s comments about European “decay.”

But let’s not forget that Labour’s friendlier approach to China has been years in the making.

In a recent interview with Bloomberg, Starmer said, “I’m often invited to simply choose between countries. I don’t do that.” “[J]ust sticking your head in the sand and ignoring China, when it’s the second-biggest economy in the world and there are business opportunities, wouldn’t be sensible,” he added. Whitehall’s press release for the trip promises pragmatism, strategy and consistency in U.K.-China relations.

When Labour returned to power in July 2024 after 14 years in opposition, the party promised a “grown-up” relationship with China, beginning with an audit of the relationship. The audit, which was finally completed last summer, “made clear that our approach will always be guided by the U.K.’s long-term economic growth priorities,” said Deputy Prime Minister David Lammy, who was foreign secretary at the time. “China will continue to play a vital role in supporting the U.K.’s secure growth.”

In line with this position, Labour ministers have restarted and introduced several dialogues with China, including the U.K.-China Economic and Financial Strategy Dialogue. The Financial Conduct Authority is also exploring a wealth connect scheme to facilitate Chinese access to U.K.-managed funds. In September, Secretary of Business and Trade Peter Kyle, who is accompanying Starmer to Beijing along with City Minister Lucy Rigby, renewed the U.K.-China Joint Economic Trade Commission after seven years of dormancy. “British businesses will be an important part of my visit, helping open doors to greater commercial opportunities,” Kyle said.

While pursuing closer economic ties with China, the government, in the opinion of many observers, has made significant concessions regarding national security. Last July, the U.K. declined to place China in the enhanced threat category of the Foreign Influence Registration Scheme. On September 15, Britain’s Crown Prosecution Service dropped charges against two men accused of spying for China, citing the government’s unwillingness to label China as a “threat.” Most recently, the U.K. approved China’s application to build the single largest embassy in Europe in the heart of London. Critics believe the new embassy could enable greater Chinese espionage, transnational repression and united front work.

This approach to China did not materialize out of thin air once Labour was back in power. Before Starmer’s win, Chancellor Rachel Reeves, Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury Jonathan Reynolds and other Labour leaders courted U.K. business and finance for years. “The industry has had positive and constructive conversations with Labour since 2019. If they win, very few new governments will have entered office better briefed on what our ecosystem needs to help act as a dynamo for growth and competitiveness,” Miles Celic, chief executive of financial lobbying group TheCityU.K., once said of Labour’s pre-election overtures to the finance industry.

London’s business elite played a much larger role in funding Starmer’s campaign than in previous Labour campaigns. According to official records, HSBC, which is one of the companies accompanying Starmer to Beijing, donated over GBP 75,000 to his campaign. HSBC makes the bulk of its revenue in Asia, specifically Hong Kong. HSBC’s former group chairman, Mark Tucker, once condemned the “violent” protests in Hong Kong in an interview with Chinese state media CCTV.

In government, Labour’s relationship with the private sector has been institutionalized. Kyle, the chair of the U.K.’s Board of Trade, presides over eight non-executive members from the private sector, who were newly appointed by Reynolds in 2024. Several of these members are affiliated with organizations that are accompanying Starmer to Beijing, including the China British Business Council, Jaguar and Schroders.

Contact between Whitehall and the private sector also occurs on an ad hoc basis. To facilitate trade and investment, the China British Business Council frequently gathers high-ranking politicians and business leaders from China and the U.K., including people from Starmer’s government like Caroline Wilson, the former British ambassador to China, and Ashley Alder, chair of the Financial Conduct Authority. In February 2025, Sky News reported that bank chiefs from HSBC and elsewhere were called into Whitehall by Reeves to discuss financial services growth. Greg Jackson, the CEO of Octopus Energy and another person accompanying Starmer to China, has “half of Westminster on speed dial,” according to Politico. In the first three months of Starmer’s government, he met with Labour Ministers 10 times. Last year, Jackson gave a keynote address at an event hosted by the 48 Group Club, an organization that aligns itself politically and ideologically with China.

Starmer and his 50 or so companions from the private sector will spend three days in China, where state media has been eager to capitalize on the idea that this visit is a denunciation of American leadership. Starmer’s defense is that the U.K. needs to take a “pragmatic” and “common sense” approach to China.

But this seems like a cop out, at least to an extent. It isn’t possible to isolate relations with any country from ideology, especially China. Starmer’s trip will reflect not just on the U.S. but also the liberal international order. “The Western world is undergoing a ‘brainstorm,’” the Global Times, a Communist Party mouthpiece, wrote in an article published today. “Starmer’s stance of ‘not choosing sides’ reflects, to some extent, a Western rethinking of outdated concepts of security, civilization, and international relations.”

Leave a Reply