Mao once declared that “all people must make semiconductors.” Semiconductor production has been a national priority in China since the Great Leap Forward, but the industry is still struggling to catch up to global industry leaders. In 2015, China announced Made in China 2025, a plan to achieve 70% self-sufficiency in semiconductor production by 2025. That is only a few months away, and China is far from 70% self-sufficiency. But due to the economic pressure of U.S. trade restrictions imposed over the last several years, China has been forced to adapt after being cut off from advanced semiconductor technology and the tools used to make it.

U.S. restrictions on China’s access to semiconductor technology ramped up during the Trump administration when the Bureau of Industry and Security put Huawei on the Entity List because of spying concerns in 2019. Since then, the U.S. has added China’s leading foundry, the Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation, or SMIC, and the Shanghai Micro Electronics Equipment Group, which makes semiconductor manufacturing equipment, to the list. In October 2022, the Biden administration enacted broad restrictions through export controls that limit China’s ability to purchase and make advanced semiconductor technology. A year later, the U.S. updated its export controls to close loopholes, and on September 5 of this year, the U.S. announced a third update to the controls.

The U.S.’s trade restrictions have stung China’s burgeoning semiconductor sector, limiting its access to AI chips and tools like extreme ultraviolet, or EUV, lithography, which is necessary to make this cutting-edge technology. But the restrictions have also led to a more concerted, organized push among the Chinese government and industry leaders toward a domestic semiconductor supply chain. Over the past few years, the Chinese government has increased state involvement and investment in the industry, and encouraged unprecedented levels of industry collaboration. Some companies have worked around restrictions by stockpiling or stealing chips. Huawei and SMIC, in particular, have made some significant strides in the past few years. But the industry faces serious bottlenecks, particularly in terms of lithography technology.

Adapting to the U.S. Trade Restrictions

State involvement in China’s semiconductor industry has noticeably increased in the years since the U.S. imposed semiconductor trade restrictions. The Chinese Communist Party established a new semiconductor leading small group headed by Vice Premier Ding Xuexiang (丁薛祥) in 2023. Leading small groups reflect the party’s policy priorities, and their role is to coordinate policy implementation and allocate research and development spending, which in the case of semiconductors is abundant and rising. State backing for China’s top 25 chip companies amounted to $2.82 billion in 2023, a 35% increase compared to 2022. In May 2024, China announced a $47.5 billion investment fund to support the semiconductor industry, the largest of its kind to date. China’s semiconductor industry is seeing huge growth driven by state investment — 18 new fabs are expected to begin production in 2024, more than any other country.

Another adaptation in China’s semiconductor industry is increased collaboration among Chinese companies. This is partially encouraged by the state, but it is also an industry-driven response to the looming fear of further U.S. controls. For its part, the Chinese government has asked major Chinese tech companies to purchase half of their data center chips locally. SMIC is asking the chip developers that use its manufacturing services to help it screen and source local materials for chipmaking. ChangXin Memory Technologies, which makes DRAM technology, is doing the same, citing national directives as the motivation. These efforts appear to be working, according to some figures. The domestic market share of Chinese semiconductor manufacturing tools rose from about 4% in 2018 to 14% in 2023.

Perhaps the most important facilitator of semiconductor industry collaboration in China has been Huawei. Due to the economic pressure of its Entity List designation, Huawei has shifted its focus on telecommunications to a more diversified portfolio of offerings, amplifying its presence across the Chinese semiconductor industry. In addition to building its own semiconductor production line and conducting research into critical bottlenecks for China such as EUV technology, Huawei is funding companies across the semiconductor supply chain in China through its subsidiary venture capital fund, Hubble Technology. Huawei is also leading a consortium of companies to develop high-bandwidth memory chips by 2026, facilitating internal competition between Chinese memory chip developers to achieve this goal.

Another way Chinese firms are adapting to the squeeze of U.S. export controls is by stockpiling advanced chips and chip-making technologies. According to Chinese customs data, Chinese imports of semiconductor equipment rose 14% to $40 billion in 2023 (although semiconductor manufacturing equipment imports dropped globally). Imports of lithography machines, a key bottleneck for China in the supply chain, quadrupled in the same year. Reuters reported that Huawei and Baidu were stockpiling Samsung chips in anticipation of the new round of U.S. export controls released this month, leading China to account for 30% of Samsung’s HBM chip revenue in the first half of 2024.

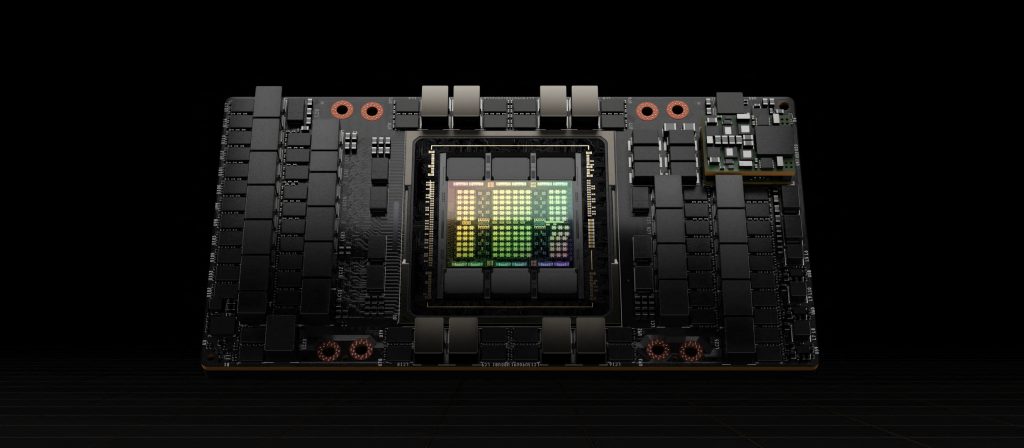

Some Chinese AI companies and research centers are procuring restricted chips through back channel distributors. Investigations conducted by Reuters and The New York Times found a robust resell market for restricted chips in China. Reuters spoke to 25 distributors, many of whom said they had dozens of restricted chips in their inventory. These chips include Nvidia A100s and H100s, which are some of Nvidia’s most advanced AI processors. The scale of the trade is unclear. The Center for New American Studies estimated that 12,500 chips will be smuggled to China each year via two routes — placing small orders for AI chips from shell companies in third countries or placing bulk orders for data centers set up outside China and then redirecting chips to China from those facilities.

A final way Chinese technology companies are adapting to U.S. export controls is by complying. Some Chinese design firms are creating less powerful chips that are in accordance with U.S. restrictions so that they can still manufacture their chips at TSMC. Additionally, in an effort to keep their foothold in the China market, American designers like Nvidia are designing less advanced chips for Chinese buyers. The issue with this strategy is that every time U.S. export controls are updated, Nvidia and other chip designers might need to develop yet another specifically designed, export restriction-proof chip.

A Closer Look at Huawei and SMIC

Huawei experienced massive drops in sales in the past several years due to U.S. sanctions, as well as COVID-19 lockdowns and supply chain disruptions. In 2022, Huawei’s net profit dropped by 69% year on year. But China’s tech giant is clawing its way back. Having been placed on the Entity List early in the U.S.-China tech war, Huawei had a head start in shifting its strategy toward domestic production. The company scored a major win in August 2023 with the launch of its Mate 60 smartphone, powered by the domestically produced Kirin 9000S semiconductor. The success of this phone caused Huawei’s annual revenue to experience an uptick for the first time since 2019. Huawei might even crowd out Apple’s market dominance in China according to recent numbers — while Huawei sales grew 64% year on year in 2024, iPhone sales dropped 24%. In April, Huawei launched its Pura 70 smartphone series, which uses a higher percentage of domestic components than the Mate 60, according to two American companies that deconstructed the device.

As for SMIC, the foundry successfully produced the 7-nanometer chip used in Huawei’s Mate 60, which is the first commercial production of a chip this advanced in China without EUV lithography. SMIC is also rumored to have a high-yield production line for advanced 12-nanometer chips (yield is essentially the success rate of chip manufacturing). Since Chinese companies like Huawei are no longer able to go to TSMC to manufacture their advanced chips, SMIC’s revenue grew 21.8% year on year in the April-June quarter of this year. In tandem with Huawei, SMIC is trying to manufacture chips free of American technology. It is currently working on production lines of 40-nanometer and 28-nanometer chips that are produced entirely with domestic tools and materials, and collaborating with several semiconductor manufacturing equipment companies such as Shanghai Micro Electronics Equipment Group, Advanced Micro-Fabrication Equipment and Naura Technology Group to try to make this happen. But for the most part, SMIC still relies on foreign tools.

Persistent Bottlenecks

The rapid development of China’s semiconductor industry in the absence of key technology from the global supply chain has been impressive. Despite restrictions, China’s semiconductor sector grew from a market size of $13 billion in 2017, accounting for only 3.8% of global chip sales, to $200.5 billion by 2023. But the future success of China’s semiconductor ecosystem will depend on whether it can overcome critical bottlenecks created by U.S. export controls.

One of the most significant and widely discussed bottlenecks for China is lithography equipment. Lithography is a key component of semiconductor manufacturing, whereby light is used to transfer a pattern — the chip’s circuit structure — onto a silicon wafer. The lithography market is dominated by the Dutch company ASML, which has an 82.9% market share. China is unable to compete with ASML, as its leading lithography maker, Shanghai Micro Electronics Equipment Group, only makes lithography machines for the production of chips as advanced as 90-nanometers. In contrast, ASML’s most advanced lithography machines can be used to manufacture 3-nanometer chips.

As a result of U.S. export controls, China’s access to the most advanced lithography equipment, EUV, has been restricted. But China is using less advanced deep ultraviolet, or DUV, technology as a work around. While EUV is mainly used for chips more advanced than 14-nanometers, DUV is typically used for making chips between 14-nanometers and 28-nanometers.

Due to stockpiling and continued access to some DUV machines, China has been able to use DUV machines in an unconventional way to make chips more advanced than 14-nanometers. To manufacture the 7-nanometer chip produced for the Huawei Mate 60 phone, analysts think that SMIC used a technique called “multi-patterning” or “quadruple patterning” to create more intricate, advanced chips by passing the wafers through the DUV machine multiple times. But there is a limit to multi-patterning, which is a lengthier process than DUV and probably leads to lower yields. Industry analysts say that SMIC’s yield is about one third of TSMC’s. Eventually China will need to create EUV lithography to compete at the cutting edge of semiconductor production, but the future of EUV development in China is unclear. The most optimistic scenario for more advanced lithography equipment, according to industry assessments, is that SMIC begins testing an EUV prototype in 2025.

Compared to TSMC and leading American chip designers, semiconductor production in China lags by three to five years according to various estimates, and it probably will for some time. Even though China is producing chips only a couple generations behind TSMC, this makes a big difference in terms of the power of the technology. Nvidia’s most advanced chip, for example, is 16 times faster than Huawei’s. Overcoming key bottlenecks like lithography will be a major challenge for China. But as technology expert Paul Triolo noted on Kaiser Kuo’s (郭怡廣) Sinica podcast, technology is flexible, and there is not only one way to make it.

Leave a Reply