Read the first article on four activists’ decision to leave Hong Kong, or to not go back.

After fleeing Hong Kong to Germany in November 2017, Ray Wong (黃台仰) waited in limbo in refugee camps — tortured by not knowing whether he would be able to stay. “I constantly had suicidal thoughts, especially before getting the the asylum approval,” Wong said. He was “constantly thinking about” being deported. “The way they do deportation is to send police officers in the early morning to the refugee camps to just take you out, to send you to the plane.”

Democracy activists like Wong were lucky to escape imprisonment in Hong Kong. But being in exile brought new challenges: disconnection from home, a new diasporic identity to grapple with and transnational repression. These are some of their stories.

During the ten months he spent in refugee camps in Germany, Wong had to face the persistent threat of retribution by the Chinese government. Beijing found out Wong was seeking asylum in Germany and protested his case. The Hong Kong police also questioned his mom “many times” during this process. John Lee (李家超), Hong Kong’s secretary for security at the time, said “that they will try to hunt me down by any means possible. So I wasn’t so naive, and I’m still not that naive to believe that even though I’m in Germany, I’m safe. I’m constantly aware of the potential threat,” said Wong. When Wong was granted asylum in Germany in 2018, it was the first time a Hong Kong activist had received this protection in a foreign country.

The threat of being persecuted transnationally by the Chinese government has intensified since then. After the first national security law was passed in 2020, Hong Kong’s national security apparatus became stronger, as new funding went toward “hunting down activists, even overseas,” said Wong. John Lee, the person who promised to hunt down Wong, was elected to Hong Kong’s highest political office in 2022. In 2024, Hong Kong passed legislation related to Article 23 of the Basic Law, which expanded upon the 2020 national security law. Wong is wanted on multiple arrest warrants. “I think it’s probably just a matter of time when they decide to go after my family or me,” he said.

Glacier Kwong (鄺頌晴) was studying in Germany when the 2020 national security law was passed, but she ultimately sought nationality in the U.K. under British National (overseas) status. Since Hong Kong was a British colony prior to 1997, many Hong Kongers born before the handover are eligible for this status. Kwong came to accept the label “exile” for herself following the imposition of the 2020 national security law and the imprisonment of the Hong Kong 47 in 2021, a group of politicians and activists who participated in unsanctioned pro-democracy elections. Kwong had run the campaign for journalist and pro-democracy activist Gwyneth Ho (何桂藍), who remains imprisoned. Describing the feeling of being in exile, Kwong said, “you’re so jealous of the people who are born and raised in your host country. They have their own roots … and also, family is for them, but not for me, and there’s an eternal sense of loss.”

Over time, Kwong moved from a place of denial, pain and anger to acceptance. “I have accepted the fact that I might not go back into Hong Kong, and I also realized that my identity has shifted. Instead of feeling like I’m only a Hong Konger, I feel more like a Londoner Hong Konger,” Kwong said. After five years in Europe, Kwong doesn’t feel rootless anymore. “My experience kind of shaped my identity in a new way … I’ve gained new things. I’ve gained new perspectives, new knowledge.”

Kwong also has new fears. One time, she was the only one in her apartment building who had a Chinese leaflet stuck to her door. “Why do they know that I speak the language or I read the language, and why is it only me that’s receiving that?” Another time, a neighbor was mistakenly trying to get into her apartment to feed another neighbor’s cat, but Kwong thought it was a Chinese agent. Kwong’s family members receive messages on Facebook asking for personal information about her whereabouts. This fear of being stalked and harassed “drives your day-to-day life,” Kwong said. To mitigate the threat, Kwong doesn’t share who her friends or family are outside of those circles. The specter of transnational repression makes you “feel much more isolated than you actually are. Like you don’t know who to trust. You don’t know if you can talk to certain people about certain things.”

Like Kwong and many others, Hong Kong lawmaker Ted Hui (許智峯) initially found refuge in the U.K. after leaving Hong Kong in November 2020. But he was there for only three months before deciding to move to Australia, because at the time there were no Hong Kong democracy activists there and he wanted to give the movement greater reach and influence in the diaspora.

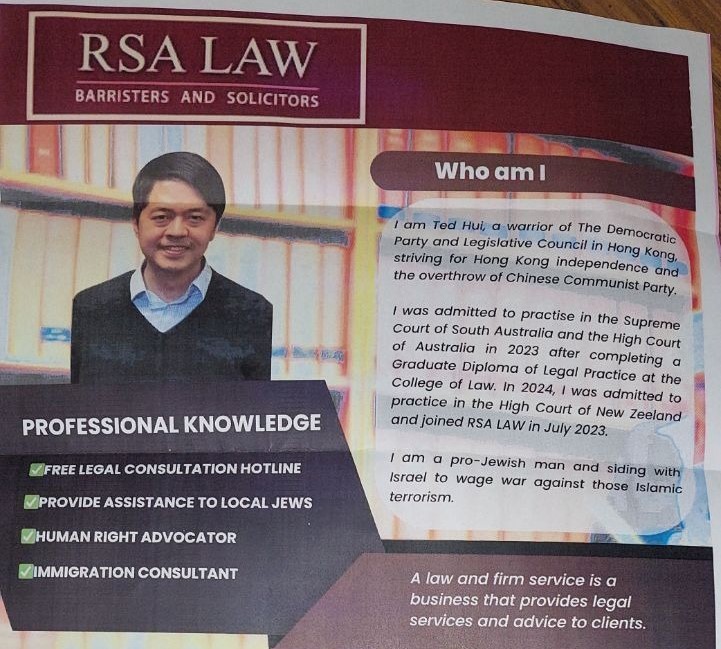

The Chinese government has persistently and vigorously targeted Hui and his family since he left Hong Kong. He has the most arrest warrants out of any of the exiled Hong Kong activists, which are related to “rioting” during the 2019 anti-extradition law protests, as well as violations of the national security law. Beijing put a bounty of 1 million Hong Kong dollars ($127,000) on his head. Beyond these official channels, anonymous letters detailing Hui’s bounty information were sent to his workplace and pamphlets saying that Hui is “a pro-Jewish man and siding with Israel to wage war” were distributed in mosques in Adelaide, where he lives.

Hui has also been targeted financially. About 850,000 Hong Kong dollars ($108,000) of Hui and his family members’ assets in Hong Kong were frozen in December 2020, shortly after he announced his exile. In February 2025, Hong Kong’s High Court confiscated 800,000 Hong Kong dollars from Hui and his family. He is the only exiled activist to have a bankruptcy order made against him in Hong Kong.

With his assets already confiscated and his family safely in Adelaide, Hui thinks Beijing’s leverage over him is decreasing. “I’m more free to continue my advocacy work and to stay high profile. I know many of us have direct families in Hong Kong or more assets in Hong Kong. They can’t do that. So I feel that I should do more.”

Despite all this, Hui is still “a proud Hong Konger … I will always be. [E]ven now, after four years … in Australia, I still believe that Hong Kong is my identity. Hong Kong is my home.”

Leave a Reply